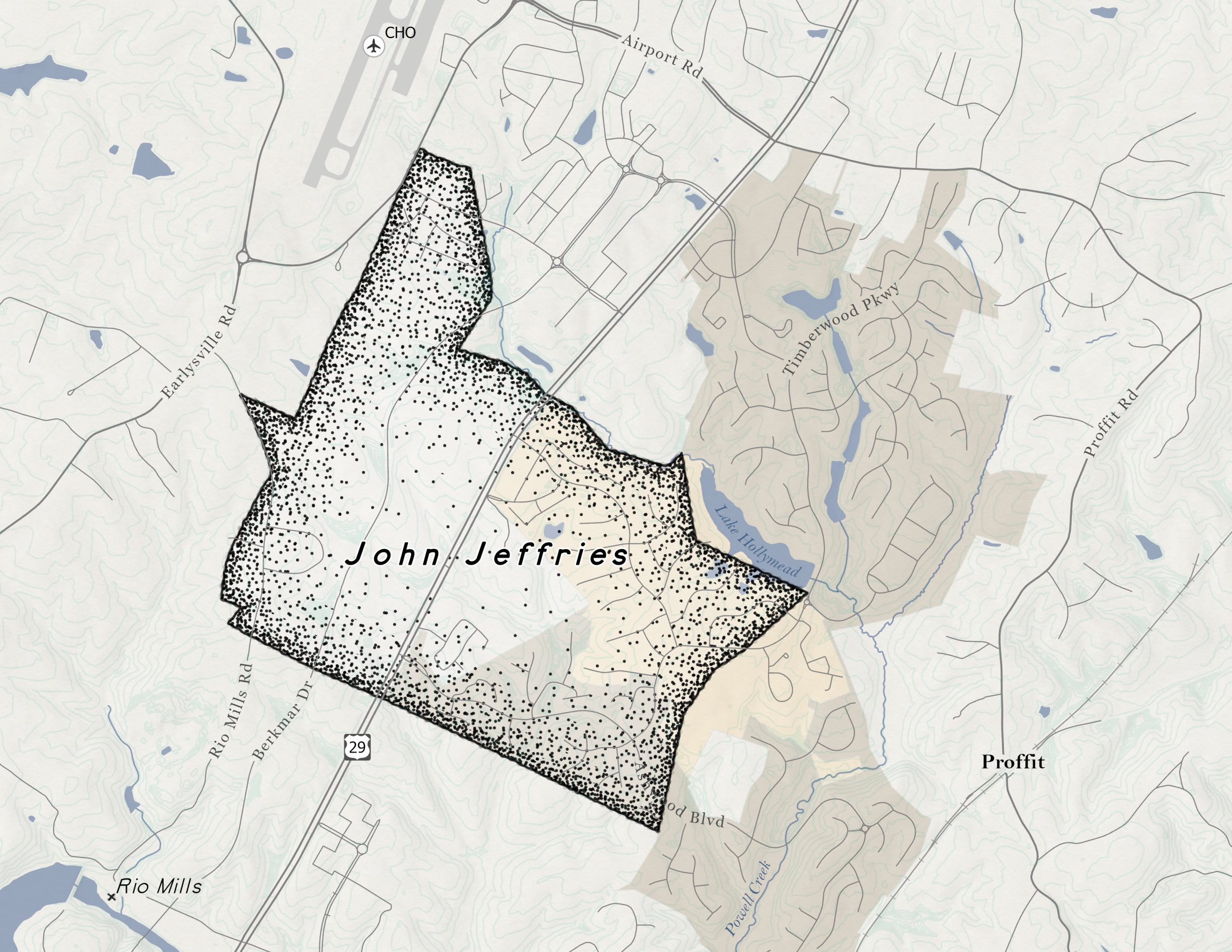

In 1813 Daniel Carr sold around 700 acres of land comprising current Hollymead and parts of Forest Lakes South to John Jeffries (Jefferies). Census and marriage records indicate that the Jeffries family, including wife Rosemond (Rosie) and children Belinda and John, relocated from Culpeper, Virginia.

Two years later, in 1815, Jeffries was directed to help maintain a road in the area. This was a common practice in this era.

“It is ordered by the court that the hands of John Jeffries be added to the gang of James Minor. Overseer of the road from Peter Carrs to Nelson Barksdales.”

The use of slave labor was also common in this era and records indicate that Jeffries was no different than most other white land owners in Albemarle County. In fact, most of the records related to his family prior to the Civil War include some mention of slavery.

In 1816 three individuals owned by Jeffries, named William, Fanny, and Rachel, were accused of “hog stealing.” They underwent an “examination”, were found guilty, and were remanded to the County jail for sentencing. The records do not show what punishment they received.

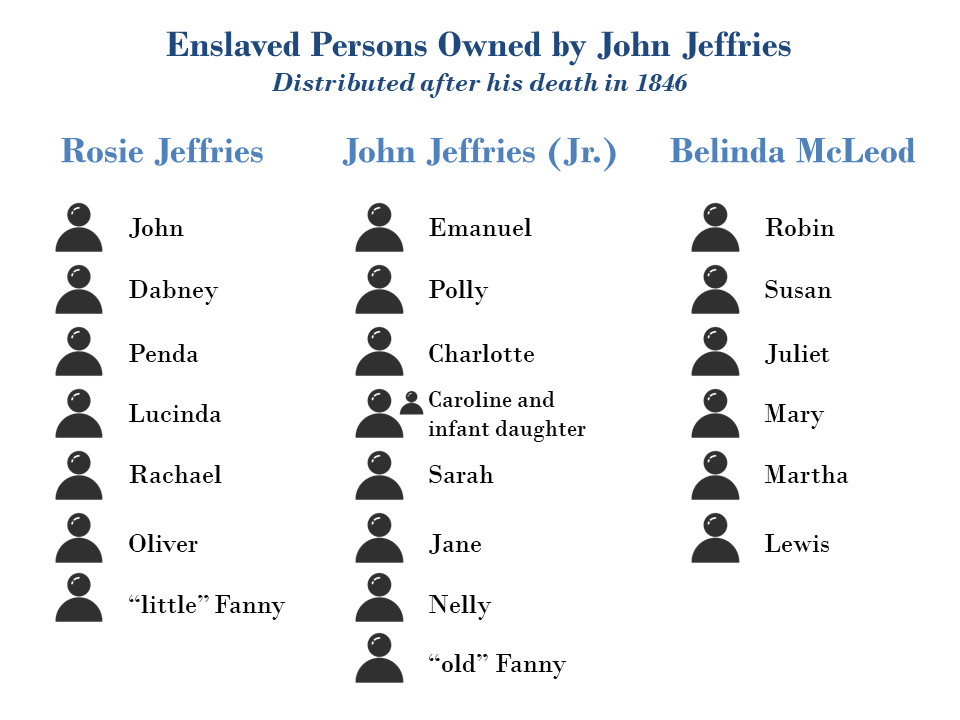

Census records from 1820-1840 show that the Jeffries household had between four and seven white persons and around 15 enslaved individuals. The enslaved were almost evenly divided between men and women and between children and adults.

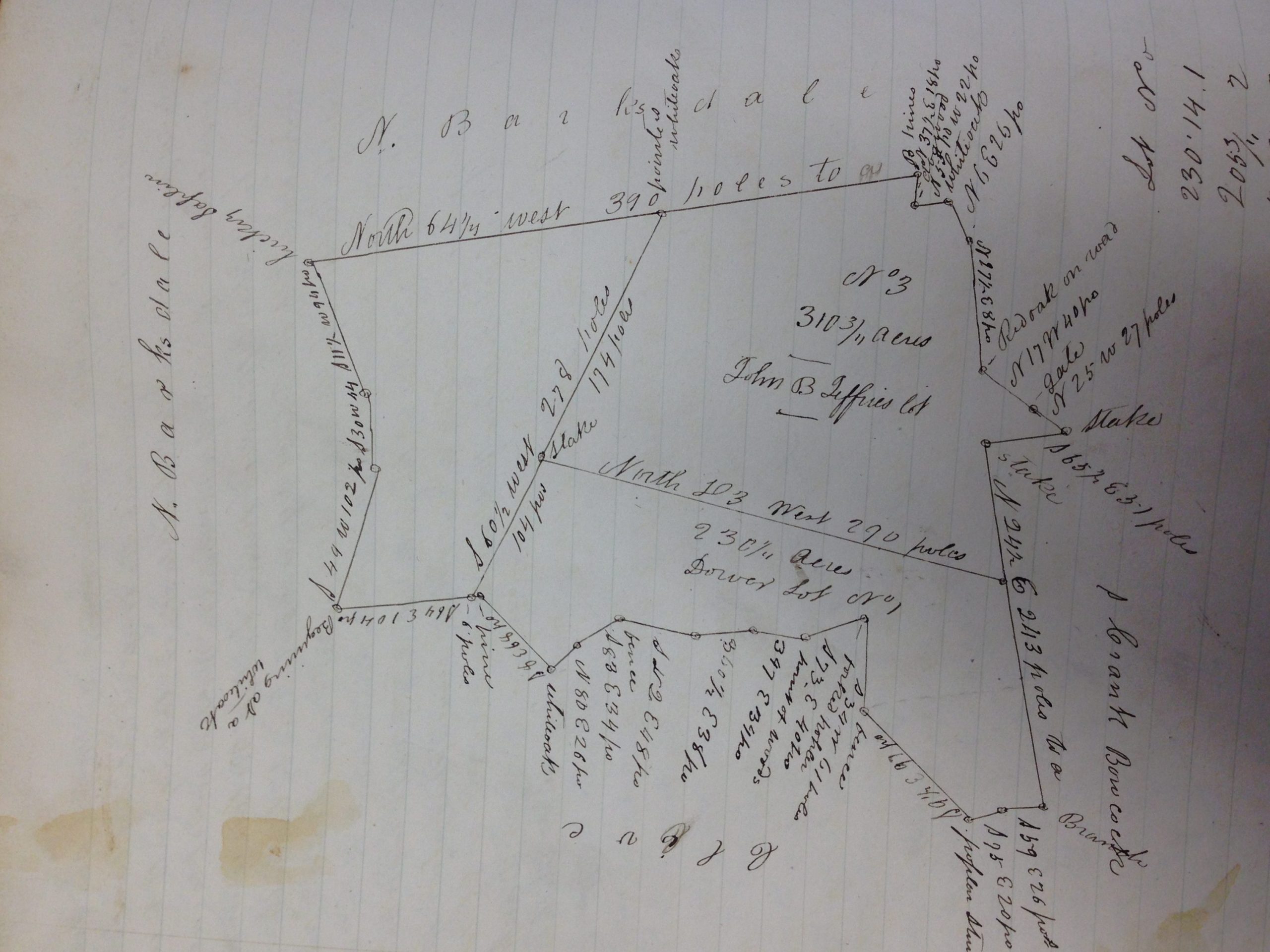

When Jeffries died in 1846 his property, including land and slaves, were divided between his wife, Rosie, and two children. This plat map is included with his will at the Albemarle County Court House:

Part of the area left to Rosie would eventually become the Hollymead subdivision and the area left to Jeffries’ daughter, Belinda McLeod, would become part of Forest Lakes South.

Legal records at the Albemarle County Court House describe how the slaves owned by John Jeffries were distributed within his family after his death.

It is possible that “old” Fanny, sent to work for John Jeffries, was the same Fanny accused of hog stealing in 1816.

In the 1850 Agriculture Census the whole farm appears to be listed under Rosie’s name. It was valued at $7500 and included 5 horses, 3 cows, 2 oxen, 50 sheep, and 40 pigs. The farm produced 3000 pounds of tobacco, 1500 bushels of corn, and smaller quantities of wheat, oats, and potatoes. The cows produced 100 pounds of butter.

In 1852 Rosie sold her share of the property to her children. They then passed ownership of the land to Belinda’s husband, John W. McLeod (Sr). The deed transferring ownership from Rosie specifies that she would “remain in quiet and peaceable possession of a negro girl Rachael”.

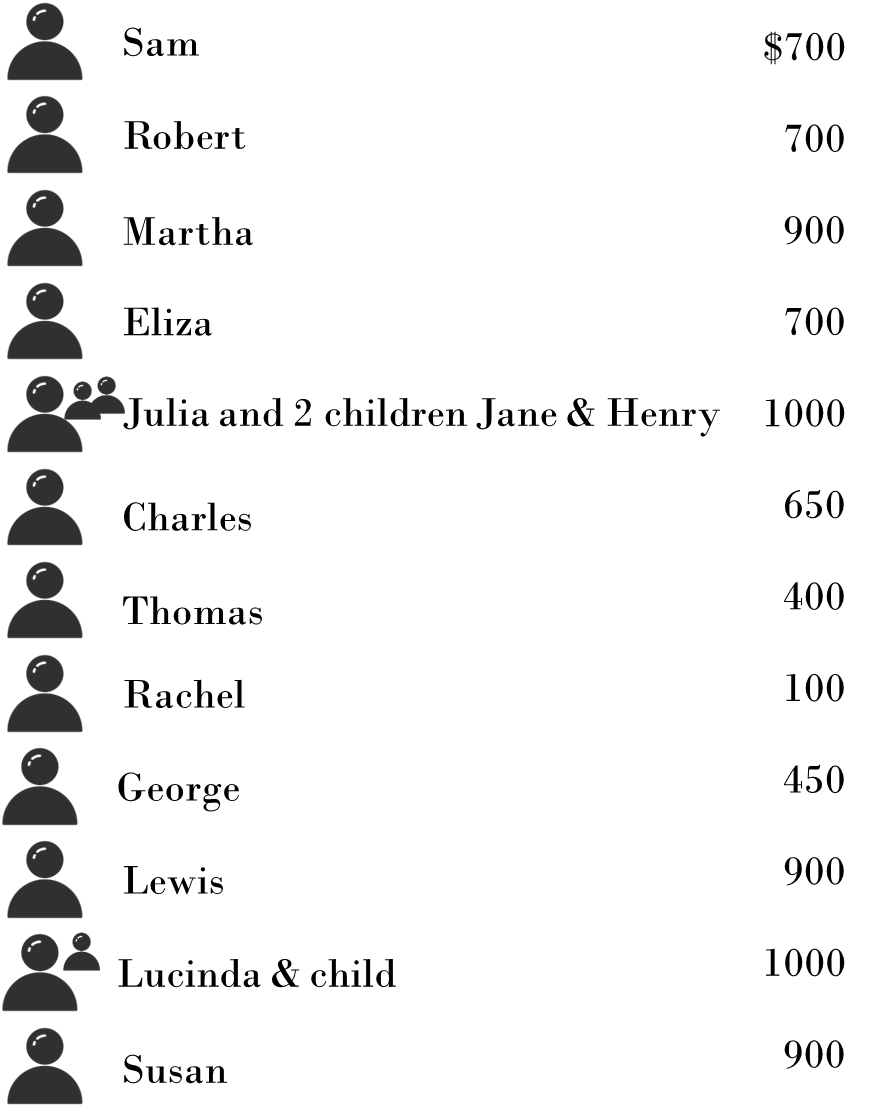

Belinda McLeod passed away in 1858. As part of the settling of her estate the names of her slaves were recorded. On a sheet of paper titled “An inventory and appraisement of property belonging to Mrs. Belinda McLeod” fourteen slaves are listed along with their estimated worth. Many of the names match slaves given to her and her mother after the death of her father.

It appears that two of enslaved women had children in the 12 years since McLeod received them. Lucinda “and child” are listed in the inventory, as well as Julia with her children Jane and Henry.

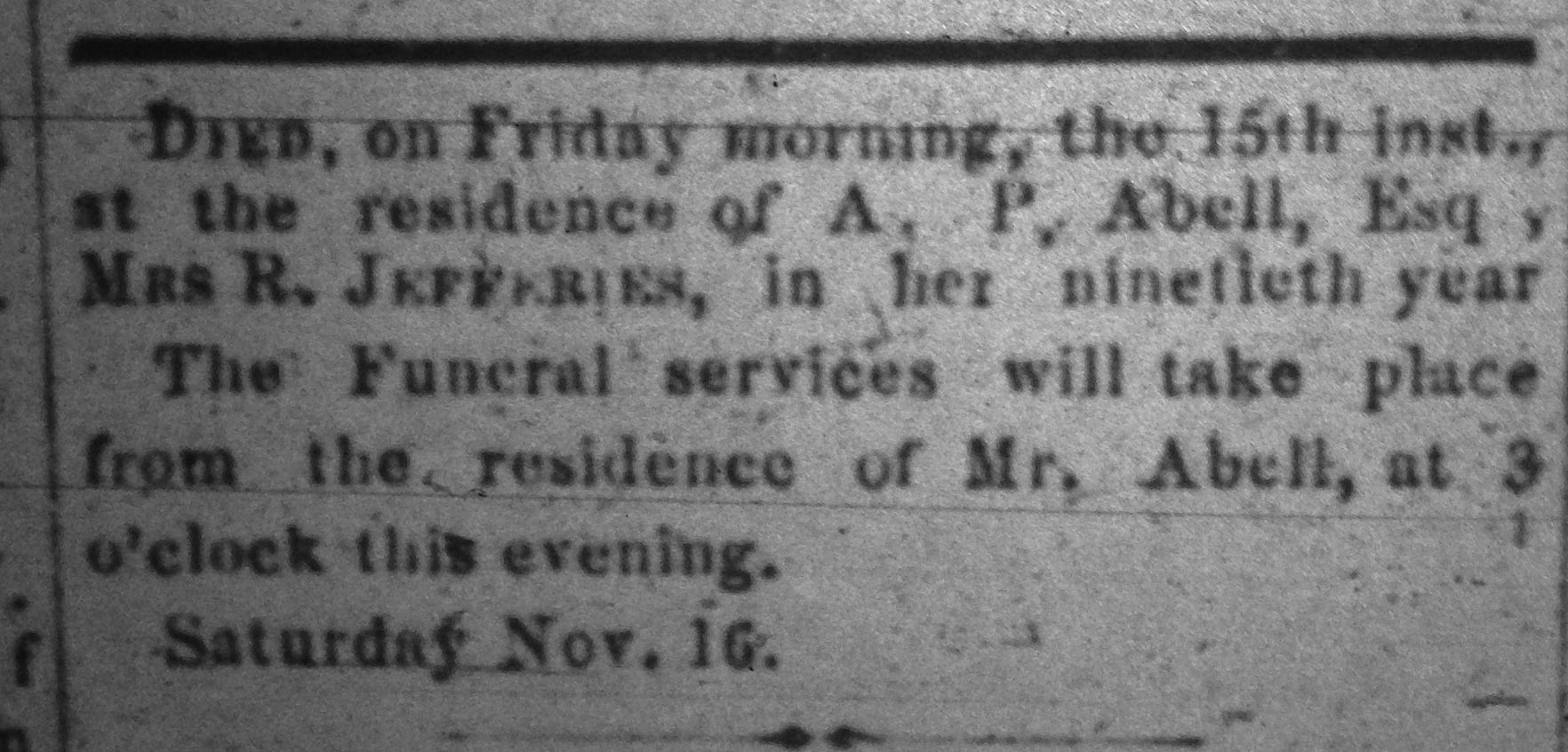

By the 1860 census Rosie was living at the home of A.P. Abell, who was married to her granddaughter, Annie. A.P. worked as a bank cashier in Charlottesville so it appears that Rosie was no longer living on the farm.

Rosie died at the age of 90 on November 15, 1867, at her granddaughter’s house. Having been born during the Revolutionary War and passing away two years after the Civil War, it’s fascinating to consider all the events and changes that Rosie witnessed during her lifetime.

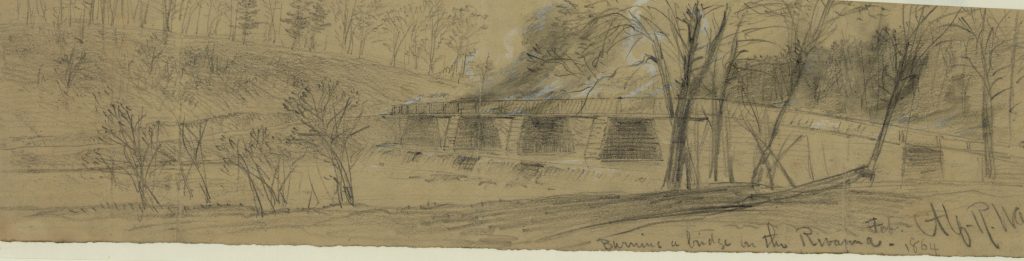

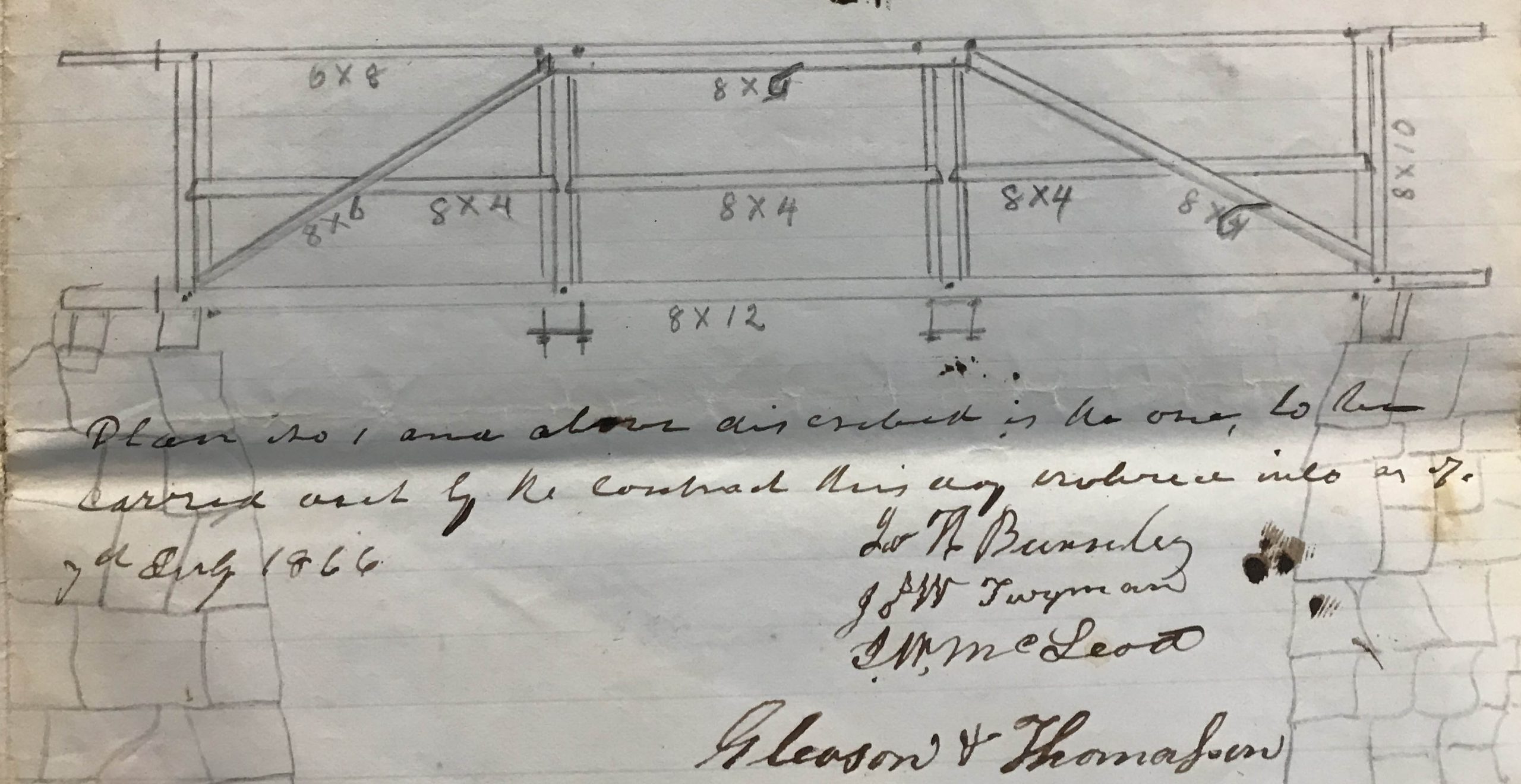

During this time period Belinda’s son, John MCleod (Jr) was living and working on the farm. Court records show that he was also designated as a road surveyor . In 1866 his name appears on documents related to the reconstruction of the Rio Bridge. The bridge crossed the Rivanna River at the site of the current dam and was destroyed by General George Armstrong Custer’s men after the “battle” of Rio Hill.

In the Spring of 1870 the County Court directed McLeod to make repairs to a culvert near the reconstructed Rio Bridge. He was also instructed to clear a new road that would eventually become what we know today as Polo Grounds Road. He was paid $1 a day for four days to establish the road, and reimbursed another $4 for the use of a plow and team of horses for two days.

By 1880 ownership of the land was divided between John W McLeod (Jr) and his sister, Annie. Agriculture records from that year show that McLeod was raising 4 horses, several cows, 12 pigs, and 50 chickens on the farm. He was growing and producing corn, oats, wheat, potatoes, tobacco, two apple orchards, bees and honey.

In 1887 McLeod helped found Laurel Hill Church, located on Proffit Road. According to a 1955 article in the Daily Progress, the church was originally used by four congregations of different denominations. McLeod was elected as a trustee representing the Baptist congregation. His neighbor, H.O. Austin, represented another congregation using the church.

The land stayed in the family’s hands for several more generations, into the 1900s.